Hello, and welcome to the Dinosaur Polo Club devlog! I hope to be updating this every week or two, assuming I can do so without it eating too much in to development time. Please get in touch via email or Twitter if you have anything specific you want to hear about, a comment to make on something I’ve posted, or if you just want to chat!

To start the devlog off, I thought I would write a short article on how it was that we came to be developing Mini Metro in the first place. Every game developer has so many ideas floating around and I find it fascinating to hear how it is that they choose which one to pour their creative energies in to.

The two of us that make up the Dinosaur Polo Club – Robert (@shiprib), and me (Peter, @peterc_nz) – have been in game development for yonks. However, outside of our work at Sidhe Interactive (we left in 2006), we haven’t shipped anything much. We’ve poured countless hours into projects that, realistically, could never have been completed. We’ve always had our heads in the sand.

It took the birth of my son last year, and the corresponding massive reduction in my free time, for me to realise that if I ever wanted to make my own games, let alone make a career out of indie game development, I had to make some serious changes in the games I attempted to develop.

So we did the dorky thing and wrote some lists. In order to get a clear idea on what sort of games we could realistically develop, we enumerated our strengths and weaknesses as developers. Here’s what we came up with:

Strengths

- Plenty of professional game programming experience.

- Web development experience.

- Good at executing simple, consistent graphic design.

- A long history of playing board games, tabletop wargames, and video games.

- Good at grokking game mechanics.

- A pedantic streak, which helps tremendously when adding the final polish to a title.

Weaknesses

- Only a handful of hours a day for development (Robert has a full-time job, I’m a stay-at-home dad).

- Zero skills at producing art assets.

- Zero music & audio skills.

- A pedantic streak, which can mean getting distracted for long periods on trivial tasks.

- No talent at PR and business, and not much drive to get better at it.

Based on the weaknesses we’d listed, we proceeded to rule out certain kinds of games that we shouldn’t even consider developing. Little time meant no hand-generated levels. The inability to generate art assets internally meant we couldn’t do anything art-heavy. And obviously we weren’t going to do anything with a strong audio component either.

Personally, one of the biggest concessions I had to make was to negate my code pedantry and perfectionism by not using an in-house game engine. I LOVE to develop engines; I love writing the low-level graphics layer, clever input frameworks, all the platform-specific glue, implementing APIs for OS-specific features like Game Center, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera. I just love it. But I’ve been doing that for years, and all I’ve ended up with is code. Lots and lots of code that does nothing that a thousand open source engines can’t do. So it was an easy choice (and an emotional one) to put my own engine development on the back burner and instead use Unity, with Matt Rix’s Futile framework.

We looked next at our strengths, and thought about what we could do with them within our constraints. Code wasn’t a problem, so levels could be procedural. A simple, abstract visual style would be possible. Consistent game rules wouldn’t be an issue once we had a concrete idea.

As often occurs, it was ironically liberating working within constraints. We were freed from considering so many choices that the ones left to us were so much clearer.

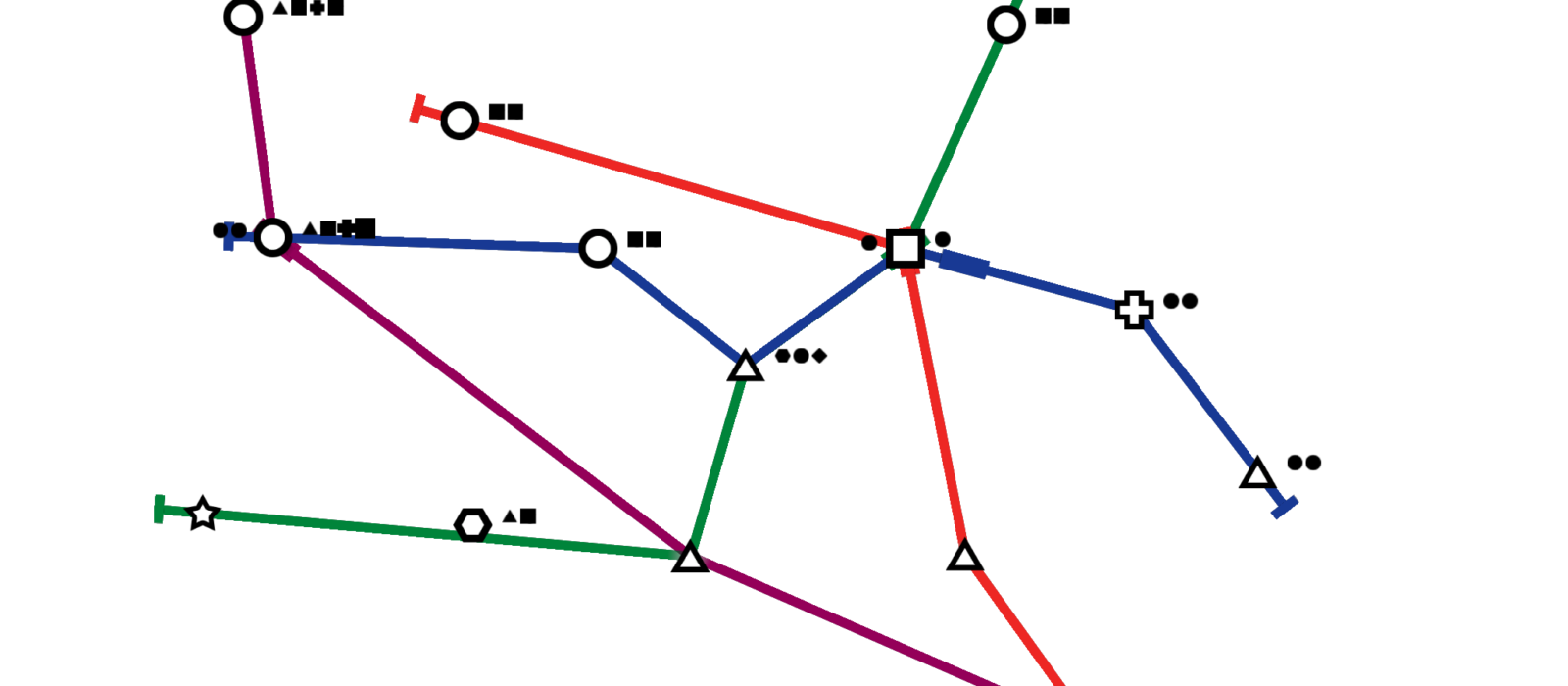

A number of ideas came to the fore, among them an abstract wargame, and a subway travelling game (almost Mini Metro in reverse). We decided to develop our first prototype during Ludum Dare 26. Doing so during a game jam was the ideal way to force us to produce a playable product, and the theme (which turned out to be, perfectly for us, minimalism) would hopefully spur some creativity.

Out of Ludum Dare came Mind the Gap, which was a direct product of playing to our strengths. Even before the end of the jam we had all-but decided to continue development, and here we are!